The insurance industry often talks about rebuild cost as if it’s a single, knowable fact - like a postcode or a floor area. But rebuild cost isn’t that kind of feature. It’s closer to a weather forecast: you can estimate it, you can explain what drives it, you can quantify confidence, and you can improve it with better inputs - but making decisions as if it’s one precise figure can often be a mistake.

That mistake matters because rebuild cost is not just an administrative detail. It quietly shapes underwriting decisions, premium adequacy, claims experience, and capital exposure. When it’s wrong, the consequences aren’t theoretical: underinsurance disputes, unexpected severity, distorted portfolio signals, and pricing that drifts away from risk.

The real question isn’t “what’s the rebuild cost?”

The question insurers actually need to answer is:

“What is the likely reinstatement cost range for this property, what drives that range, and how should we act on that uncertainty?”

A point estimate can be useful. But it’s rarely sufficient for portfolio decisions - and it’s often actively misleading when it comes with a false sense of precision.

Why rebuild costs behave differently at scale

In a single-property context, it’s understandable to reach for a standardised calculator-style approach. It gives a quick answer and a familiar workflow.

At portfolio scale, that same approach starts to creak - not because it’s “wrong”, but because it’s designed for a different job. Underwriting and pricing need rebuild costs to be:

Segmentable (so you can explain differences between properties, not just accept them)

Traceable (so pricing and risk teams can defend outputs)

Complete (so you don’t routinely miss scope)

Honest about uncertainty (so edge cases don’t pollute decisions)

Consistent across millions of properties (so you can build stable models)

This is where insurers typically find the limits of “one number”.

Finish quality: the silent multiplier

Two properties can share the same size, type, and location - and still sit in materially different reinstatement realities. Finish quality changes the materials, workmanship, and specification that rebuilding would require.

In practice, insurers don’t need a philosophical debate about “luxury”. They need a pragmatic way to represent finish variation that is:

consistent,

scalable, and

usable in pricing and underwriting.

That’s why rebuild needs to behave more like a segmentation problem than a single-value lookup.

Materials and labour don’t move together (and neither should your model)

In the real world, rebuild inflation doesn’t arrive as a uniform uplift. Materials markets and regional labour markets can diverge - sometimes sharply. If an insurer can’t see the composition of a rebuild estimate, it becomes harder to do the work that matters:

stress testing,

inflation scenario planning,

and explaining changes in exposure over time.

A “decision-grade” approach doesn’t just output a total. It treats the total as the sum of drivers - because that’s how risk teams manage reality.

Outbuildings: small on paper, large in claims friction

Outbuildings are one of the most common sources of rebuild cost underestimation. They’re easy to overlook, variable in size and type, and often bundled into generic assumptions.

At scale, generic assumptions become systematic bias. And systematic bias becomes either:

creeping underinsurance, or

premiums that drift away from actual reinstatement exposure.

If a rebuild approach doesn’t explicitly model outbuildings as reinstatement scope, the insurer is effectively choosing to be less accurate in a place that customers notice most after an event.

The uncomfortable truth: uncertainty isn’t a nuisance, it’s information

Most rebuild approaches treat uncertainty as an afterthought - a single confidence range, if anything at all. But uncertainty isn’t uniform across the housing stock. Construction type, non-standard methods, and specialist requirements change both expected cost and confidence.

For underwriting teams, this is operational gold:

higher uncertainty can trigger smarter referral rules,

outliers can be triaged rather than silently accepted,

and pricing can be robust without being blunt.

A good rebuild model doesn’t pretend uncertainty disappears. It makes uncertainty usable.

Coverage isn’t a feature - it’s a pricing requirement

A lot of the pain in rebuild modelling comes from the tails of the distribution: high-value properties, listed buildings, and commercial stock. These aren’t just “edge cases”; they’re often where exposure is concentrated and where claim severities can bite.

Portfolio-grade rebuild intelligence needs to cover the parts of the market where insurers most need clarity - not just the tidy middle.

The direction of travel: rebuild as a living view of the property

Properties change. Extensions, conversions, refurbishments, and upgrades don’t wait for an insurer’s next data refresh cycle. Planning signals, physical characteristics, and observable change matter because they shift reinstatement exposure.

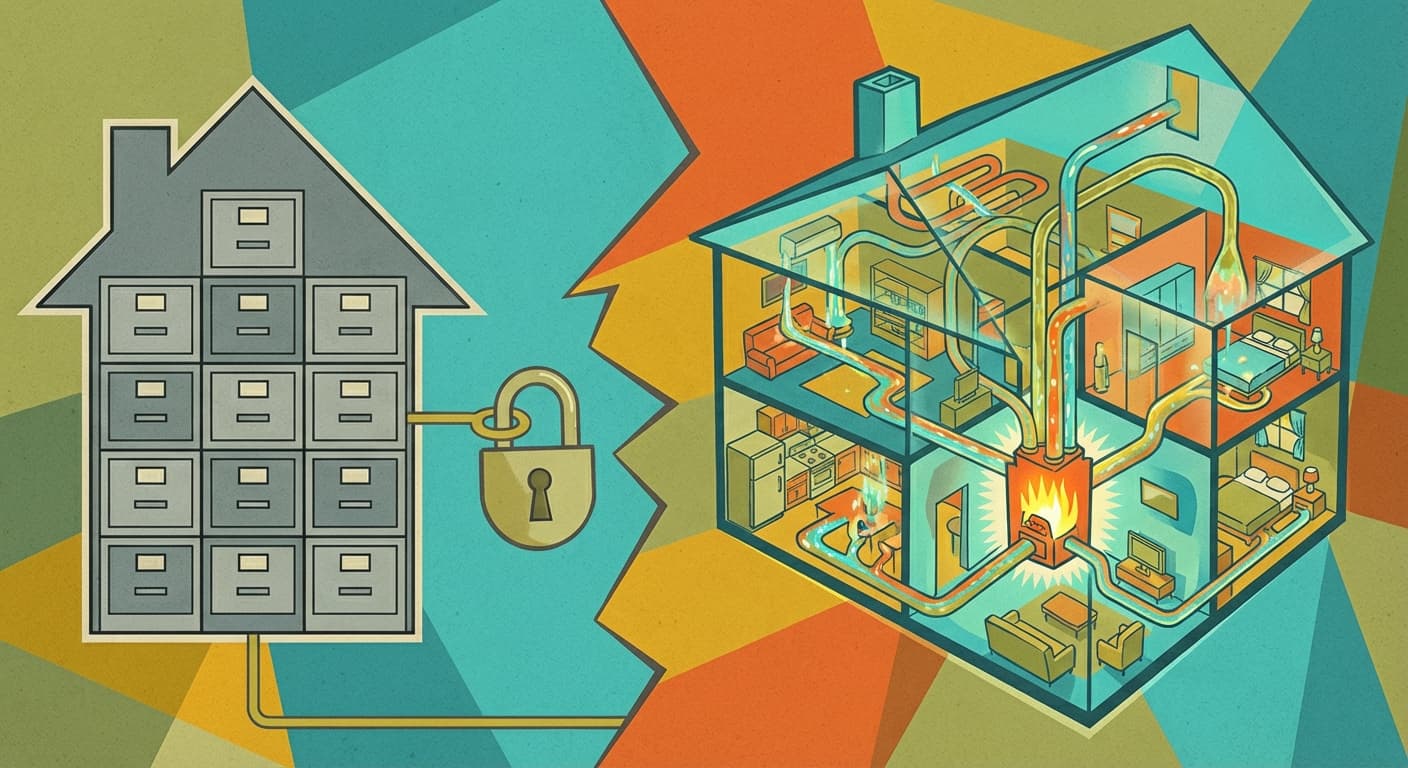

In that sense, rebuild cost is not a static attribute. It’s a living view of what would likely need to be rebuilt - and under what constraints - if the worst happens.

What “better” looks like (without chasing false precision)

The end goal isn’t to produce the most impressive-looking single number. The goal is to produce rebuild cost intelligence that is genuinely usable in insurance decisions:

A structured representation of quality (so reinstatement is not flattened into averages)

Transparent cost drivers (so the model can be governed and stress tested)

Explicit scope including outbuildings (so risk is not systematically understated)

Construction-aware uncertainty (so operational decisions are better, not noisier)

Reasonableness and outlier controls (so the portfolio behaves)

A path to adoption that supports like-for-like comparison when needed

In other words: a system, not a calculator.

Because in underwriting, the competitive edge rarely comes from claiming you have “the” answer. It comes from building a better way to make decisions when the answer is inherently uncertain.